A Question of Tribe – Kenya und seine Ethnien/ and its tribes

german/english version Nicht erst seit den jüngsten Konflikten in Äthiopien ist die Frage der Zugehörigkeit zu einer Ethnie eine sehr vorherrschende Frage in Afrika. A question of Tribe, das ist nicht nur in Kenia eine wichtige Sache, das zeigt uns Lorna Likiza in ihrem Essay für cultureafrica.net. Tribe, im Deutschen gerne auch mit Stamm übersetzt, assoziert immer auch etwas Volkstümlich, Archaisches. Volksgruppe oder Ehnie ist der wohl passendere Begriff. Allein in Kenia sind es mehr als 40 davon, die 50 und mehr Sprachen sprechen.

Es gibt drei Hauptgruppen: die bantusprachigen, die nilotischen und die kuschitschsprachigen Volksgruppen. Diese drei wiederum haben Untergruppen.Der größte Teil der Einwohner Kenias gehört den bantusprachigen Volksgruppen an. Die größte davon ist die Gruppe der Kikuyu mit 22% Anteil, die Luhya (14%), Kamba (11%), Kisii (6%), Mijikenda (5%) und Meru (4%). Zu den bekanntesten, der eher kleinen Volksgruppen gehören die Massai, die allerdings mit 2% eher zu einer Minderheit gehören. (alle Daten von: wikipedia)

Not only since the recent conflicts in Ethiopia has the question of ethnic affiliation been a very prevalent issue in Africa. A question of Tribe, this is not only an important thing in Kenya, Lorna Likiza shows us in her essay for cultureafrica. net. Tribe, in German also often translated as Stamm, always associates something folkloric, archaic. Ethnic group or ehnie is probably the more appropriate term. In Kenya alone, there are more than 40 of them, speaking 50 or more languages. There are three main groups: the Bantu-speaking, the Nilotic and the Kushitsch-speaking ethnic groups. These three in turn have subgroups. The majority of Kenya’s inhabitants belong to the Bantu-speaking ethnic groups. The largest of these is the Kikuyu group with 22% share, the Luhya (14%), Kamba (11%), Kisii (6%), Mijikenda (5%) and Meru (4%). Among the best known of the rather small ethnic groups are the Maasai, who are, however, with 2% rather a minority. (all dates from:wikipedia)

For the English Version of the Essay, please scroll down.

“Aber von welchem Stamm ist sie?” Insistierte sie auf Suaheli, als sie mir gegenüber saß.

Ich war von der Organisatorin zu diesem runden Tisch Anfang 2020 eingeladen worden, der eigentlich eine kulturelle Diskussion im Players Theatre in Nakuru war, einem kolonialen Relikt, das in den späten 40er Jahren gebaut wurde, um der weißen Kolonialbevölkerung zur Theaterunterhaltung zu dienen. Ich kam spät an, fand alle sitzend vor und war die letzte Person, die sich vorstellte. Aber in der Minute, in der ich meinen Nachnamen sagte, begann diese Dame, die ich schon ein paar Mal im Art Studio in der Bibliothek gesehen, aber noch nie mit ihr gesprochen hatte, mich mit Fragen zu löchern.

Wie so viele andere, die ich zuvor getroffen hatte, löste mein zweiter Name immer Fragen über meinen Stamm aus. Clevererweise hatten meine Eltern bei meiner Geburt zwei Swahili-Wörter miteinander kombiniert und sich so meinen Namen ausgedacht. Später entdeckte ich, dass er für die Menschen, die ich traf, immer eine Doppeldeutigkeit darstellte, vor allem, weil er nicht einem bestimmten Stamm zugeordnet werden konnte. Hartnäckige Fragen, zu welchem Stamm ich gehöre, seit ich sehr jung war und in der Gesellschaft meiner Eltern, immer gefolgt von unaufgeforderten Analysen, hatten dazu geführt, dass ich gleich nach der Highschool anfing, mich mit meinem ersten englischen Namen vorzustellen. Aber als ich reifer wurde, entdeckte ich, dass mein zweiter Name niemals die Frage beantworten würde, die viele beantwortet haben wollten, und so war ich auf das Geplänkel dieser Dame bestens vorbereitet.

Interessanterweise fühlten sich alle anderen Anwesenden zum ersten Mal sichtlich unwohl mit ihrem Drängen, was sie kaum bemerkte. Vielleicht lag es daran, dass ich mich inmitten von kunstsinnigen Menschen befand, die sich mehr um den Ausdruck kümmerten als darum, aus welchem Stamm ich stammte. Aber in diesem angespannten Moment, als ich sie ansah, konnte ich sofort erkennen, dass sie aufrichtig neugierig war. Dann dämmerte mir, dass es absolut nichts damit zu tun hatte, absichtlich beleidigend zu sein, sondern dass es eher eine kenianische Konditionierung war, den Stamm, oder besser die Ethnie von jemandem automatisch an seinem zweiten und dritten Namen zu erkennen.

Ruhig erklärte ich ihr, was mein Name bedeutet, in der Annahme, dass sie damit zufrieden sein würde. Sie war aber noch nicht fertig. Sie wollte immer noch meinen genauen Stamm wissen und ich antwortete ihr ebenfalls. Danach beruhigte sie sich, während alle anderen sichtlich erleichtert aufatmeten, dass der unangenehme Moment endlich vorbei war. Während des gesamten Gesprächs sagte sie sehr wenig und ich entdeckte, dass sie eigentlich ein sehr schüchternes Mädchen war. Als es kurz nach dem Treffen zu regnen begann, liefen wir zusammen in einen Unterschlupf und tauschten auch Nummern aus.

Monate später finde ich diese Interaktion immer noch ziemlich amüsant. Die Erwartung aller anderen an diesem Tag war, dass ich schnell beleidigt sein würde, nur dass ich mit unerwarteter Ruhe reagierte. In der Tat hätte dies für jeden eine unangenehme Situation sein können. Überraschenderweise war sie es für mich zu diesem Zeitpunkt nicht. Im Laufe der Jahre hat sich die Identifizierung nach Stammeszugehörigkeit in Kenia zu einem sensiblen Thema entwickelt, dem man viel Aufmerksamkeit schenken sollte, auch wenn man nicht damit rechnet, beleidigt zu werden.

Als ich in einem Wohnheimzimmer auf dem Campus lebte, war ich entsetzt und beschämt zugleich, als ein Mädchen so schnell ausziehen musste, wie sie eingezogen war, weil sie sich bei uns nicht willkommen fühlte, weil sie einer anderen Ethnie angehörte. Es spielte keine Rolle, dass ich nicht ganz einer Ethnie angehörte, sondern die Tatsache, dass ich die besagte Umgangssprache verstand, wenn sie von meinen Mitbewohnern gesprochen wurde, dann war ich einer von ihnen und sie nicht. Es wäre etwas, das mich jedes Mal in stille Verlegenheit versetzte, wenn ich ihr auf dem Korridor begegnete; die Tatsache, dass wir alle versagt hatten, diesem neuen Mädchen das Gefühl zu geben, willkommen zu sein, wenn wir es konnten.

Die Angst und der Verdacht, dass man von anderen nicht akzeptiert werden kann oder riskiert, anders angesehen zu werden, ist das, was die Aussage, welchem Stamm man angehört, bei einem ersten Treffen zu etwas macht, das viele lieber vermeiden würden. Anstatt eine Identität zu sein, die es uns ermöglicht, unsere Wurzeln leicht zurückzuverfolgen, wird der Stamm zunehmend dazu benutzt, zu spalten und zu unterdrücken. Als Kenianer können wir die Schuld nicht allein auf die britischen Kolonialisten schieben, deren Strategie es war, zu teilen (zuerst nach Rasse und dann nach Ethnie) und zu herrschen. Kenia ist seit über 55 Jahren ein unabhängiger Staat, aber die Frage nach der Ethnie und den Privilegien, die er einem gewährt (oder eben nicht), besteht bis heute.

Ein gewisses Maß an Selbstreflexion der kenianischen Gesellschaft ist dringend erforderlich. Es ist notwendig, zuerst neu zu definieren, was Ethnie für uns als Individuen bedeutet, und dann die bewusste Entscheidung zu treffen, die Ethnie nicht mehr zu benutzen, um unsere Bedürfnisse zu befriedigen, sondern als eine positive Feier unserer Vielfalt. Letzteres scheint zum jetzigen Zeitpunkt unerreichbar zu sein, ist aber in naher Zukunft tatsächlich möglich, wenn wir uns gemeinsam dafür einsetzen, dass dies geschieht.

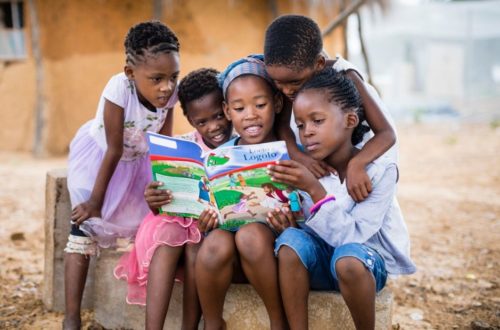

Es fängt damit an, dass wir unsere Kinder ermutigen, einander wirklich zu umarmen, unabhängig von der Ethnie.

Lorna Likiza ist Autorin und Gründerin der heroebookfair, die dieses Jahr in Mombasa stattfinden wird. Sie lebt in Nakuru, Kenia.

THE QUESTION OF TRIBE

By Lorna Likiza

“But from which tribe is it?” She insisted in Swahili, sitting across from me.

I had been invited by the organizer to this round table early 2020 that was actually a cultural discussion at the Players Theatre, Nakuru, a colonial relic built in the late 40s to serve the white colonial population’s theatrical entertainment. I arrived late, found everyone seated and was the last person to introduce myself. But the minute I said my last name, then this lady I had seen a couple of times before at the Art Studio in the library but never spoken to, began firing questions at me.

Like so many others I had met before, my second name always elicited questions about my tribe. Cleverly, my parents had combined two Swahili words communicating the time I was born and come up with my name. I later discovered that it would always be an ambiguity to people I met and largely because it could not be placed in a particular tribe. Persistent questions on which tribe I was, from the time I was very young and in the company of my parents, always followed by unsolicited analysis had led me to start introducing myself with my first English name immediately after high school. But as I matured, I discovered that my second name would never answer the question many wanted answered and so, I was very prepared for this lady’s badgering.

Interestingly, for the first time, everyone else present was visibly uncomfortable with her insistence which she barely realized. Perhaps it was because I was in the midst of artsy people who cared more about expression than on which tribe I came from. But in that tense moment as I looked at her, I could immediately tell that she was genuinely curious. It then dawned on me that it had absolutely nothing to do with being intentionally offensive, rather it was more of a Kenyan conditioning to automatically tell someone’s tribe from their second and third name.

Calmly, I explained to her what my name meant assuming it would satisfy her. She was not done yet. She still wanted to know my exact tribe and I answered her as well. She settled down after that while everyone else visibly breathed a sigh of relief that the uncomfortable moment was finally past us. Throughout the discussion, she said very little and I discovered that she was actually a very shy girl. We ended up running together for shelter when it began to rain soon after the meeting and exchanged numbers too.

Months later, I still find this interaction rather amusing. The expectation by everyone else that day was for me to quickly get offended only for me to react with unexpected calm. Indeed, this could have been an uncomfortable situation for anyone. Surprisingly, it wasn’t for me at this point in time. Over the years, the identification by tribe in Kenya has morphed into a sensitive subject worth paying considerable attention to no wonder the expectation of offense being taken.

Living in a hostel room in campus, I was horrified and at the same time ashamed, when a girl had to move out as quickly as she had moved in because she did not feel welcomed by us being of a different tribe. It did not matter that I wasn’t entirely one tribe but the fact that I understood the said vernacular when it was spoken by my roommates, then I was one of them and she was not. It would be something that caused me silent embarrassment every time I bumped into her on the corridor; the fact that we had all failed to make this new girl feel welcome when we could.

The fear and suspicion that one cannot be accepted by others or risks being viewed differently is what makes saying which tribe you are on a first meeting something many would rather avoid. Instead of being an identity that enables us to easily trace our roots, tribe has increasingly been used to divide and subdue. As Kenyans, we cannot entirely lay the blame on the British Colonialists whose strategy was to divide(on the basis of first, race and then, tribe) and rule . Kenya has been an independent state for over 55 years but the question of tribe and the privileges it can afford you (or lack of) continues to persist to date.

Some level of introspection by Kenyan society is much needed. There is an inherent need to first re-define what tribe means to us as individuals and then, make that conscious decision to cease using tribe to serve our needs but rather, as a positive celebration of our diversity. Indeed, the latter seems unattainable at this juncture but is actually possible in the near future if we collectively purpose to ensure it happens.

It starts with us encouraging our children to genuinely embrace each other regardless of tribe. It starts with that Kenyan in a voting booth ticking besides a candidate’s name and political party not because they speak the same vernacular language and come from the same place but because their track record is one of integrity. It starts with Swahili being used in situations where the vernacular language would have been the chosen pick because we are conscious that a minority in our midst may not understand our mother tongue. It starts with us totally dropping stereotypical views of different tribes and having the courage to shun nepotism when our position tempts us to lean on it.

As Kenyans, we are fully aware of just what negative ethnicity can do to a nation. We have witnessed countries in East Africa suffer immense devastation on the basis of tribe. Rwanda is never far from our minds when we speak of this. The same has been replicated to a smaller scale in our country but for the particular Kenyan communities which were directly affected it wasn’t to a small scale for them. The 2007/2008 Post Election Violence in Kenya threatened to go bigger but a repeat is not only prevented by reminders but a driven and genuine purpose to change our collective mindsets for the greater good.

Lorna Likiza is a writer and founder of the heroebookfair. She lives in Nakuru, Kenya.