Akono Publishing and Blog – Spot on Africa: Afrikanische Literaturen und Kultur sichtbar machen – Interview – ger/engl

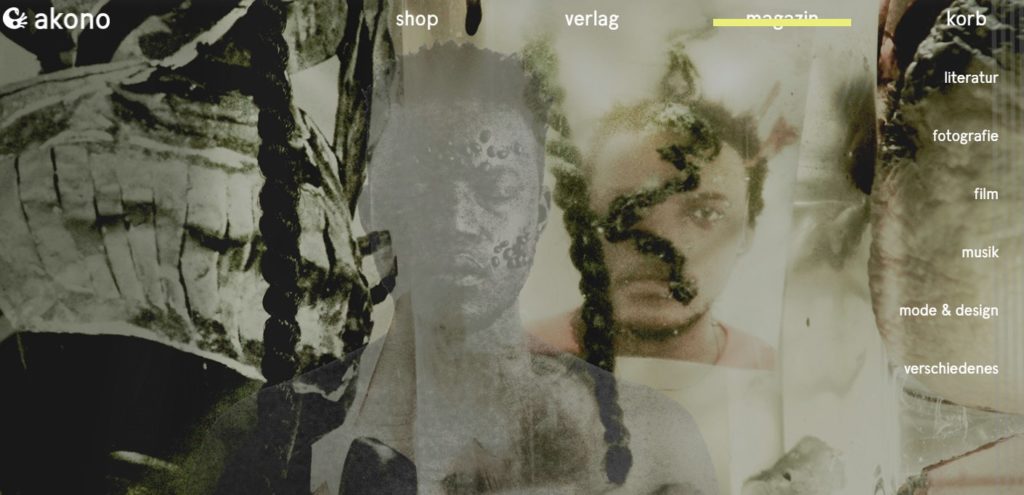

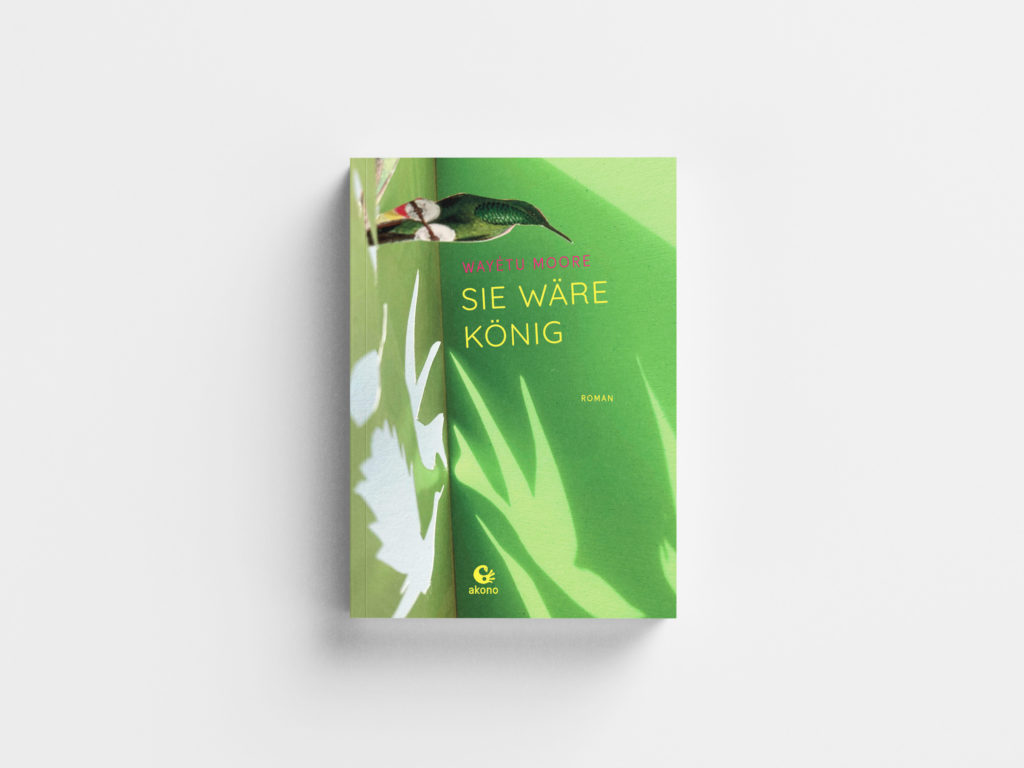

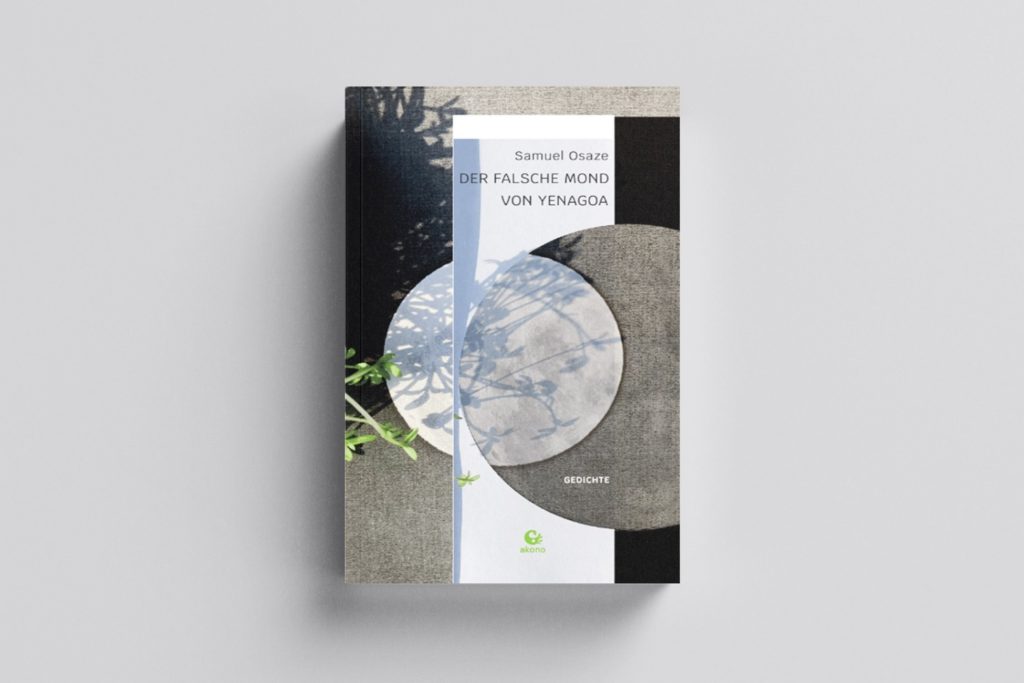

Der Akono Verlag Leipzig hat sich der Verbreitung von afrikanischer Kultur im deutschsprachigen Raum zum Ziel gesetzt. Neben einem Blog ist Akono seit letztem Jahr auch verlegerisch tätig: drei Bücher der zeitgenössischer Autor:Innen Samuel Osaze, Bronwyn Law-Viljoen und Wayétu Moore hat der Leipziger Verlag frisch heraus gebracht. Ein kleines, feines Programm. Auch dieses Jahr stehen einige Neuerscheinungen an. Max Lobe ist neuer Autor im Verlag. Hinter dem Verlag steht Jona Elisa Krützfeld. Sie hat einige Jahre in afrikanischen Ländern gelebt und hat mit dem Verlag noch viel vor. Der Blog veröffentlicht vielfältige und interessante Texte afrikanischer Autor:Innen auf Deutsch und wie es akono selbst sagt: “zeigt ihre Perspektiven, Stile und Geschichten und würdigt die ästhetischen Ausdrucksformen globaler afrikanischer Kreativität in Literatur, Fotografie, Mode, Design, Musik und Film.”

Für cultureafrica.net hat Hans Hofele in Leipzig nachgefragt und Jona Elisa online zum Gespräch getroffen.

Hans Hofele: Jona, was hat dich dazu bewogen, den akono Verlag zu gründen; es ist ja ungewöhnlich, einen Verlag zu gründen oder nicht? War es die Folge einer längeren Entwicklung?

Jona Elisa Krützfeld: Es war eine lange Entwicklung, die sich über mehrere Jahre hingezogen hat. Es gibt eine kurze und eine lange Geschichten dazu. Die kurze ist, dass die Verlagsgründung eine Kombination aus dem ist, was ich für wichtig halte, und dem was ich gerne mache. Sie hat sich aber auch biografisch ergeben, weil ich in verschiedenen afrikanischen Ländern gelebt habe, auch dort gearbeitet habe und oft in afrikanischen Buchläden war und afrikanische Literaturen gelesen habe, von denen ich gemerkt habe, dass es sie auf Deutsch noch nicht gibt. In erster Linie ist das eine Übersetzungsthematik. Es hat auch mit der Kolonialgeschichte zu tun, dass viele Auror:Innen auf Englisch, Französisch oder Portugiesisch und eben in afrikanischen Sprachen schreiben, aber nie auf deutsch. Wenn man also in Deutschland Literatur von afrikanischen Autor:Innen haben möchte, dann muss die übersetzt werden.

Weil ich beruflich von den Kulturwissenschaften und Afrikastudien komme, war es mir ein Anliegen, kulturelle Bildung über Literatur zu betreiben.

Denn es gibt dort immer noch Repräsentationsschieflagen: der Literaturkanon muss dekolonisiert werden, deutsche Afrikadiskurse sind leider immer noch kolonialrassistisch und exotisierend geprägt.

Es geht dann viel um wirtschaftliche Faktoren, um Migrationspolitik, um „Entwicklungshilfe“, seltener geht es um kulturelle Dinge.

Mir war es wichtig, über die Literatur afrikanische Lebensrealitäten darzustellen und daran mitzuwirken, dass diese Literaturen übersetzt werden. Historische Fiktion ist ein Schwerpunkt im Verlagsprogramm, afrikanische Perspektiven aus Afrika und nicht aus Europa.

HH: Dein Ausgangspunkt war also die Feststellung, dass da ein starkes Ungleichgewicht herrscht in der Betrachtung über Afrika. Dass Betrachtungen aus Afrika in Deutschland unterrepräsentiert sind.

JK: Ich denke, dass eine Aufgabe meiner Generation ist, daran mitzuwirken, dass das imperiale Erbe Europas dekolonisiert wird. Die Geschichte des Kolonialismus hat die Kulturen, die Geschichte und das Wissen über Afrika nicht nur unterjocht, sondern auch verfälscht. Ich verorte mich bei dieser Gemeinschaftsaufgabe auf der kulturellen Ebene und habe die Literatur dafür gewählt. Das ist die negative Betrachtung. Man kann sich natürlich auch positiv auf die Sache beziehen, was ich auch sehr gerne mache: warum afrikanische Literaturen ausgerechnet? Ich als Leserin finde in afrikanischen Literaturen sehr viel Erleuchtung und neue Perspektiven. Durch die „entwicklungspolitische“ Betrachtung geraten andere Dinge wie afrikanische Literaturen aus dem Blickfeld.

HH: Du sprichst immer von afrikanischen Literaturen im Plural, wieso?

JEK: Afrikanische Literatur im Singular ist keine zulässige Kategorie, dazu sind die verschiedenen Strömungen zu heterogen, zu viele Genres, zu viele Stile in 55 Ländern. Man kann aber schon sagen, dass sich afrikanische Literaturen durch Zirkulation und Zerstreuung auszeichnen, durch Interaktion, Vermischung und Grenzüberschreitung, durch Überlagerung von verschiedenen Kulturen und Sprachen. Deswegen sind afrikanische Literaturen so spannend, weil sie sich auch aus verschiedenen oralen Traditionen speisen und von verschiedenen Realitäten informiert sind. Das macht sie extrem lebendig, oft sehr humorvoll.

“Warum afrikanische Literaturen ausgerechnet? Ich als Leserin finde in afrikanischen Literaturen sehr viel Erleuchtung und neue Perspektiven.”

HH: Ist das Beschäftigen mit Afrika immer noch etwas exotisch in Deutschland? Wie ist das bei dir? Bei französischer oder amerikanischer Literatur werden vermutlich nicht so viel Fragen gestellt.

JEK: Ich habe noch keine richtige Antwort darauf, wie viel sich tatsächlich wo mit „Afrika“ beschäftigt wird. Ich befinde mich, glaube ich, in einem Zwischenraum. Auf der einen Seite gibt es eher althergebrachte Diskurse, die Afrika hauptsächlich mit Armut und Krieg in Verbindung bringen. Auf der anderen Seite hat sich ganz viel verändert. Da gibt es ganz andere Diskurse. Und die sozialen Medien spielen dabei eine große Rolle: Über Instagram, Tumblr, Facebook werden auch neue visuelle Erzählungen verbreitet. Erzählungen von Afrikaner:Innen und nicht über sie. Hier findet also auch eine Dekolonisierung der Bilderwelten, ein Aufbrechen der Sehgewohnheiten statt, wie ich sie auch im akono Onlinemagazin adressiere. Zum ersten Mal in der Geschichte haben wir ganz viele visuelle Erzählungen von Afrikaner:Innen selbst. Erzählungen, die zeigen sollen, wie sie sich selber darstellen wollen.

Soziale Medien machen es einem einfach: Da findet man einen DJ aus Nairobi, den man auf soundcloud gefunden hat, einen Fotografen aus Lagos, den man von Instagram kennt. Es gibt eine Gleichzeitigkeit, die stattfindet, natürlich gibt es auch eine fähige ältere Generation, die sich mit Afrika beschäftigt; es braucht aber auch frischen Wind einer jungen Generation.

HH: Du meinst mit der älteren Generation ambitionierte Verlage wie Peter Hammer oder den Wunderhorn Verlag. Verlage, die sich schon früh mit afrikanischen Literaturen befasst haben und auch verlegen. Es gibt aber auch Bewegungen, die irgendwann in den letzten Jahrzehnten stehen geblieben sind und die Veränderungen wie zum Beispiel die Wichtigkeit von social media nicht gesehen haben.

JEK: Diese Verlage haben extrem gute und wichtige Arbeit geleistet. Es braucht immer etwas Erneuerung, um alte Diskurse aufzuweichen, alte Dichotomien aufzulösen. Auch um zu zeigen, dass die moderne Welt extrem miteinander verwoben ist. Europäische Modernität war schon immer von afrikanischen Kulturen beeinflusst und ist es immer noch. Afrikanische Musik ist überall global, Literatur ist es auch. Es geht aber auch darum, das geistige Eigentum von Afrikaner:Innen in Deutschland wertzuschätzen und auch soweit, wie es in einem Miniverlag möglich ist, zu kompensieren. Dafür ist dieser Verlag gedacht. Ich habe ja vorhin erwähnt, dass historische Fiktion ein Schwerpunkt ist. Ich mache aber auch dieses Jahr eine Anthologie über Liebe und Begehren. Da sind auch queere Geschichten enthalten. Auch das Onlinemagazin ist an einer Ästhetik orientiert, die Afro Bubblegum heißt, ein Begriff der geprägt wurde von Wanuri Kahiu aus Kenia, das ist eine Ästhetik, die afrikanische Künstler:Innen transportieren, deren Arbeiten fun, fierce and frivolous sind. Die Arbeit von zeitgenössischen afrikanischen Künstler:Innen in Literatur, Fotografie, Musik, Film, Mode und Design. Akono soll auch eine Plattform für die Darstellung dieser Arbeiten sein.

HH: Wenn wir mal auf dein Programm gehen, du bist mit drei Büchern gestartet (Sie wäre König, Der Nachlass des Grafikers und Der falsche Mond von Yenagoa ). Wie kam es zu dieser speziellen Auswahl und ist es generell schwer, die Rechte zu erwerben?

JEK: Es ist nicht schwer, Werke zu finden, die es wert sind, übersetzt zu werden. Es gibt eine große Zahl an Werken, die auf Englisch, Französisch oder Portugiesisch erschienen sind. Es gibt aber auch viel wichtige Literatur, Klassiker, zeitgenössische Literatur, die in afrikanischen Sprachen erschienen sind, an die ich jetzt noch nicht so rankomme. Allein aus dem anglophonen Raum gibt es sehr viele Werke, die ich gerne übersetzen lassen würde. Als neuer Verlag stößt man bei Literaturagent:Innen erstmal auf Skepsis. Deswegen konnte ich mir nicht ganz frei aussuchen, was ich übersetzen wollte. Ich mache vor allem Scouting, ich lese also viel und schaue, was machbar wäre.

Der Roman Sie wäre König, der die Geschichte Liberias behandelt, hat mir einfach wahnsinnig gut gefallen und ich fand das Thema wichtig. Dann habe ich die Agentur angefragt und auch den Zuschlag bekommen.

Es gibt einen Gedichtband, der neu herauskam, das ist zum Beispiel ein Freund aus Lagos, der Gedichte schreibt. Und manchmal melden sich auch Übersetzer:innen mit eigenen Projekten.

HH: dann kommt ja eine Schwierigkeit: Bücher sind übersetzt und hergestellt. Jetzt müssen sie aber auch die Leser:Innen erreichen. Ist da social media auch eine Hilfe? Denn in deutschen Buchhandlungen sind afrikanische Bücher ja nicht besonders gut vertreten. Kannst du zu den Schwierigkeiten etwas sagen?

JEK: Prinzipiell finden Leute die Bücher erst mal sehr interessant. Der Verkauf läuft in erster Linie über den Webshop auf meiner Seite, wofür ja Social Media enorm wichtig ist. Ich glaube, der Buchmarkt strukturiert sich generell etwas um, das hat möglicherweise auch mit der Pandemie zu tun, Leute bestellen mehr online, auch direkt beim Verlag. Das Marketing ist anders, wieder spielt Social Media eine Rolle. Es hängt mit Buchhandelsstrukturen zusammen, dass es manchmal schwierig ist als Außenseiter und Newbee. Es ist sehr viel Arbeit, an die Buchhandlungen heranzutreten und die Leute von den eigenen Büchern zu überzeugen, wenn man auf eigene Faust agiert. Das Angebot ist einfach riesig und man muss auch erstmal den Takt verstehen, nach dem alles läuft.

HH: Wir haben in Deutschland und im deutschsprachigen Raum die Tradition der Autor:Innen Lesungen. Das kann ja mitunter Eventcharakter annehmen. Menschen zahlen Eintritt um die Autor:Innen zu hören. In der Pandemie wurde auch dieses Erlebnis immer wieder eingeschränkt, Buchmessen verschoben oder Online durchgeführt. Hat das auch auf akono seine Auswirkungen gehabt?

JK: Lesungen sind prinzipiell sehr wichtig. Mit Max Lobe, der in Europa lebt, den ich neu im Verlag habe, planen wir wahrscheinlich eine Lesereise. Da freue ich mich wirklich drauf. Durch die Republik zu ziehen und Lesungen zu veranstalten. Das ist schon wichtig, dass man auch den persönlichen Austausch hat. Ansonsten finden Lesungen meist über Zoom statt, was ein wenig entfremdet ist. Büchertische können dort auch nicht gemacht werden.

HH: Das Jahr 2021 war ja für afrikanische Autor:Innen ein außergewöhnlich erfolgreiches Jahr. Viele wichtige Literaturpreise gingen nach Afrika und die Diaspora. Was bedeutet das für dich, wie schätzt du das ein?

JK: Der Literaturnobelpreis, der Booker Prize, Prix Goncourt, Friedenspreis… Ob das ein Strohfeuer ist, kann ich nicht abschätzen. Es gab ja immer wieder mal ein Interesse an afrikanischen Literaturen, danach ist es etwas abgeebbt. Ich hoffe, dass es diesmal etwas nachhaltiger ist.

HH: Fängt nicht schon bei der Besetzung der Kulturinstitutionen, bei den Verlagen selbst, auch bei Zeitungs- und Fernsehredaktionen, wo auch immer, das Bild an schief zu werden, wenn dort PoC unterrepräsentiert sind? Uns eingeschlossen?

JK: Ich glaube, dass wir uns in einem Zwischenzustand befinden. Natürlich ist der Idealzustand, dass PoC vor und hinter der Kamera stehen, Verlage führen, Feuilletons dirigieren. Es muss eine Massenanstrengung sein, dort hinzukommen. Weiße Menschen müssen sich ständig selbst reflektieren, Critical Whiteness, Weiterbildung muss stattfinden. Ich würde gerne meinen Verlag, wenn er soweit auf eigenen Beinen steht, dass man davon leben kann, an eine Person of Color übergeben, wenn sich jemand Geeignetes findet, der oder die Lust auf diese Arbeit hat.

Wie ist das bei dir. Erfährst du Kritik dafür, dass du als weißer Mann diese Arbeit machst?

HH: Das ist ein Veränderungsprozess. Je mehr ich mit den Menschen aus Afrika direkt zu tun habe, quasi auf Augenhöhe spreche, Wertschätzung zeige, desto weniger Vorbehalte bekomme ich. Das war und ist auch ein Lernprozess. Die eigenen Vorstellungen hinterfragen, den eurozentristischen, weißen Blick hinterfragen. Mit afrikanischen Autor:Innen und Kulturschaffenden, Blogger:Innen zusammenarbeiten, das schafft Vertrauen. Viele Fragen sind zum Beispiel Schlicht monetärer Natur. Afrikanische Autor:Innen sind darauf angewiesen, dass ihre Arbeit; sei es Lesung, Beitrag, Rezensionsexemplar bezahlt werden. Da nutzt es nichts zu sagen, dass man selbst Non-Profit ist. Es geht gerade auch in der Kultur um die Existenz. Es gibt keinen doppelten Boden wie bei uns.

JK: In meiner Arbeit können meine Position und mein Blickwinkel problematisch werden, wenn es um die Auswahl der Inhalte geht. Aber auch jetzt gerade, wenn ich mich als Expertin für afrikanische Literatur darstellen soll, was ich nicht bin. Das versuche ich auch kritisch zu betrachten, da kann ich auch Fehler machen. Ich versuche ja Inhalte zu verbreiten und nicht Inhalte zu kreieren. Auch im akono Magazin zum Beispiel:

Ich habe dafür Fördergelder organisiert, damit die Perspektiven, Ästhetiken und Geschichten von Kulturschaffenden übersetzt und dargestellt werden. Ich agiere mehr im Hintergrund. Es ist ein Prozess der „on going“ ist.

HH: Was hast du, hat sich der akono Verlag für dieses Jahr vorgenommen?

JK: Mit einem Übersetzer zusammen wird eine Anthologie herauskommen mit Kurzgeschichten über Liebe und Begehren. Es wird noch einen historischen Roman geben aus Burundi, der vom letzten König dort am Hof erzählt. In einer Zeit, in der arabische und deutsche Truppen in das Land vordringen. Es handelt vom Leben am Hof, von der Gesellschaftsordnung, alles aus burundischer Sicht. Ein Lyrikband ist am Entstehen. Es wird also drei Romane geben, eine Anthologie mit Kurzgeschichten und den Lyrikband. Kurzgeschichten sind ja nicht so ganz einfach in Deutschland, da bin ich gespannt, wie die ankommen.

HH: Jona, ich danke dir für das Interview.

Hans Hofele ist Herausgeber von cultureafrica.net

ENGLISH VERSION

ENGLISH VERSION

Akono Verlag Leipzig has set itself the goal of disseminating African culture in German-speaking countries. In addition to a blog, Akono has also been publishing since last year: three books by contemporary authors Samuel Osaze, Bronwyn Law-Viljoen and Wayétu Moore have just been published by the Leipzig publishing house. A small, fine programme. This year, too, there are several new publications in the pipeline. Max Lobe is a new author at the publishing house. Jona Elisa Krützfeld is behind the publishing house. She has lived in African countries for several years and has many plans for the publishing house. The blog publishes diverse and interesting texts by African authors in German and, as akono itself puts it: “shows their perspectives, styles and stories and appreciates the aesthetic expressions of global African creativity in literature, photography, fashion, design, music and film.”

HH: Jona, what made you decide to found akono Verlag; it is unusual to found a publishing house, isn’t it? Was it the result of a longer development?

JEK: It was a long development that took several years. There is a short story and a long story about it. The short one is that starting a publishing house is a combination of what I think is important and what I like to do. But it also came about biographically because I have lived in various African countries, also worked there, and often went to African bookshops and read African literatures that I realised were not yet available in German. First and foremost, it’s a translation issue. It also has to do with colonial history that many authors write in English, French or Portuguese and in African languages, but never in German. So if you want to have literature by African authors in Germany, it has to be translated.

Because my professional background is in cultural studies and African studies, it was important to me to do cultural education about literature.

Because there are still representational imbalances there: the literary canon has to be decolonised, German discourses on Africa are unfortunately still colonially racist and exoticising.

It is then much about economic factors, migration policy, “development aid”, less often about cultural things.

It was important to me to present African realities of life through literature and to work towards translating these literatures. Historical fiction is a focus in the publishing programme, African perspectives from Africa and not from Europe.

HH: So your starting point was the observation that there is a strong imbalance in the way Africa is viewed. That perspectives from Africa are underrepresented in Germany.

JK: I think that one of the tasks of my generation is to help decolonise Europe’s imperial heritage. The history of colonialism has not only subjugated but also distorted cultures, history and knowledge about Africa. I locate myself in this community task on the cultural level and have chosen literature for this. That is the negative view. Of course, you can also look at it positively, which is what I like to do: why African literatures of all things? As a reader, I find a lot of enlightenment and new perspectives in African literatures. By looking at them “developmentally”, other things like African literatures get out of focus.

HH: You always speak of African literatures in the plural, why?

JEK: African literature in the singular is not a permissible category, the different currents are too heterogeneous, too many genres, too many styles in 55 countries. But one can say that African literatures are characterised by circulation and dispersion, by interaction, mixing and crossing borders, by the overlapping of different cultures and languages. That’s why African literatures are so exciting, because they also feed on different oral traditions and are informed by different realities. That makes them extremely lively, often very humorous.

HH: Is dealing with Africa still somewhat exotic in Germany? How is it with you? With French or American literature, people probably don’t ask as many questions.

JEK: I don’t really have an answer yet to how much “Africa” is actually dealt with and where. I find myself, I think, in an in-between space. On the one hand, there are more traditional discourses that associate Africa mainly with poverty and war. On the other hand, a lot has changed. There are completely different discourses. And social media play a big role in this: new visual narratives are also being spread via Instagram, Tumblr, Facebook. Narratives of Africans:inside and not about them. So a decolonisation of the visual worlds, a breaking of visual habits, is also taking place here, as I also address in the akono online magazine. For the first time in history, we have a lot of visual narratives from Africans themselves. Narratives that are meant to show how they want to portray themselves.

Social media makes it easy: you find a DJ from Nairobi you found on soundcloud, a photographer from Lagos you know from Instagram. There is a simultaneity that takes place, of course there is also a capable older generation that is concerned with Africa; but there also needs to be a breath of fresh air from a younger generation.

HH: By the older generation, you mean ambitious publishers like Peter Hammer or Wunderhorn Verlag. Publishers that were involved with African literatures early on and also publish them. But there are also movements that have stood still at some point in the last decades and have not seen the changes, such as the importance of social media.

JEK: These publishers have done extremely good and important work. It always needs some renewal to soften old discourses, to dissolve old dichotomies. Also to show that the modern world is extremely intertwined. European modernity has always been influenced by African cultures and still is. African music is global everywhere, literature is too. But it is also about valuing the intellectual property of Africans in Germany and compensating for it as much as is possible in a mini-publishing house. That is what this publishing house is for. I mentioned earlier that historical fiction is a focus. But I’m also doing an anthology on love and desire this year. There are also queer stories in it. The online magazine is also oriented towards an aesthetic called Afro Bubblegum, a term coined by Wanuri Kahiu from Kenya, which is an aesthetic conveyed by African artists whose work is fun, fierce and frivolous. The work of contemporary African artists in literature, photography, music, film, fashion and design. Akono is also meant to be a platform for the presentation of this work.

HH: Moving on to your programme, you started with three books (She Would Be King, The Graphic Designer’s Estate and The False Moon of Yenagoa ). How did that particular selection come about and is it generally difficult to acquire the rights?

JEK: It is not difficult to find works that are worth translating. There are a large number of works that have been published in English, French or Portuguese. But there is also a lot of important literature, classics, contemporary literature that has been published in African languages that I can’t get to yet. There are many works from the Anglophone world alone that I would like to have translated. As a new publisher, Frahling:Innen is initially met with scepticism. That’s why I couldn’t choose freely what I wanted to translate. I mainly do scouting, so I read a lot and see what would be feasible.

I just really liked the novel She Would Be King, which deals with the history of Liberia, and I thought the subject was important. Then I approached the agency and also got the nod.

There is a book of poetry that has just come out, for example, a friend from Lagos who writes poetry. And sometimes translators come forward with their own projects.

HH: Then there is a difficulty: books have been translated and produced. But now they have to reach the readers. Is social media also a help here? Because African books are not particularly well represented in German bookshops. Can you say something about the difficulties?

JEK: In principle, people find the books very interesting at first. Sales are primarily via the web shop on my website, for which social media is enormously important. I think the book market is restructuring a bit in general, that might also have something to do with the pandemic, people are ordering more online, also directly from the publisher. Marketing is different, again social media plays a role. It has to do with book trade structures that it is sometimes difficult as an outsider and newbee. It’s a lot of work to approach bookshops and convince people to buy your books when you go it alone. The offer is simply huge and you first have to understand the pace at which everything works.

HH: In Germany and in the German-speaking world, we have the tradition of author readings. That can sometimes take on the character of an event. People pay admission to hear the authors. During the pandemic, this experience was also repeatedly restricted, book fairs were postponed or held online. Has that also had an impact on akono?

JK: Readings are very important in principle. We are probably planning a reading tour with Max Lobe, who lives in Europe and is new to my publishing house. I’m really looking forward to that. To travel through the republic and organise readings. That’s important, that you also have the personal exchange. Otherwise, readings usually take place on Zoom, which is a little alienating. Book tables can’t be done there either.

HH: The year 2021 was an exceptionally successful year for African authors. Many important literary prizes went to Africa and the diaspora. What does that mean for you, how do you assess it?

JK: The Nobel Prize for Literature, the Booker Prize, Prix Goncourt, Peace Prize… I can’t judge whether it’s a flash in the pan. There was always some interest in African literature, but after that it died down a bit. I hope that this time it will be more sustainable.

HH: Doesn’t the picture already start to become skewed in the staffing of cultural institutions, in the publishing houses themselves, also in newspaper and television editorial departments, wherever, when PoC are underrepresented there? Including us?

JK: I think we are in an in-between state. Of course, the ideal state is that PoC are in front of and behind the camera, running publishing houses, directing feuilletons. It has to be a mass effort to get there. White people need to constantly self-reflect, Critical Whiteness, continuing education needs to happen. I would like to hand over my publishing house to a person of colour when it is sufficiently self-supporting to make a living, if someone suitable can be found who wants to do this work.

How is it with you? Do you receive criticism for doing this work as a white man?

HH: It is a process of change. The more I have direct contact with people from Africa, speak at eye level, so to speak, and show appreciation, the fewer reservations I get. That was and is also a learning process. Questioning one’s own ideas, questioning the Eurocentric, white view. Working together with African authors and cultural workers, bloggers, creates trust. Many questions, for example, are simply monetary in nature. African authors depend on being paid for their work, be it readings, articles or review copies. It is no use saying that you are a non-profit. Especially in culture, it is a matter of existence. There is no double bottom like there is with us.

JK: In my work, my position and my point of view can become problematic when it comes to choosing content. But also right now, when I am supposed to present myself as an expert on African literature, which I am not. I also try to look at that critically, I can also make mistakes. I try to disseminate content and not to create content. Also in akono magazine, for example:

I have organised funding for it so that the perspectives, aesthetics and stories of cultural workers are translated and presented. I act more in the background. It is a process that is “on going”.

HH: What do you, akono Verlag, have planned for this year?

JK: Together with a translator, an anthology will be published with short stories about love and desire. There will also be a historical novel from Burundi about the last king at court there. At a time when Arab and German troops were advancing into the country. It is about life at court, about the social order, all from a Burundian perspective. A book of poetry is in the making. So there will be three novels, an anthology of short stories and the poetry collection. Short stories are not so easy in Germany, so I’m curious to see how they are received.

HH: Jona, thank you for the interview.