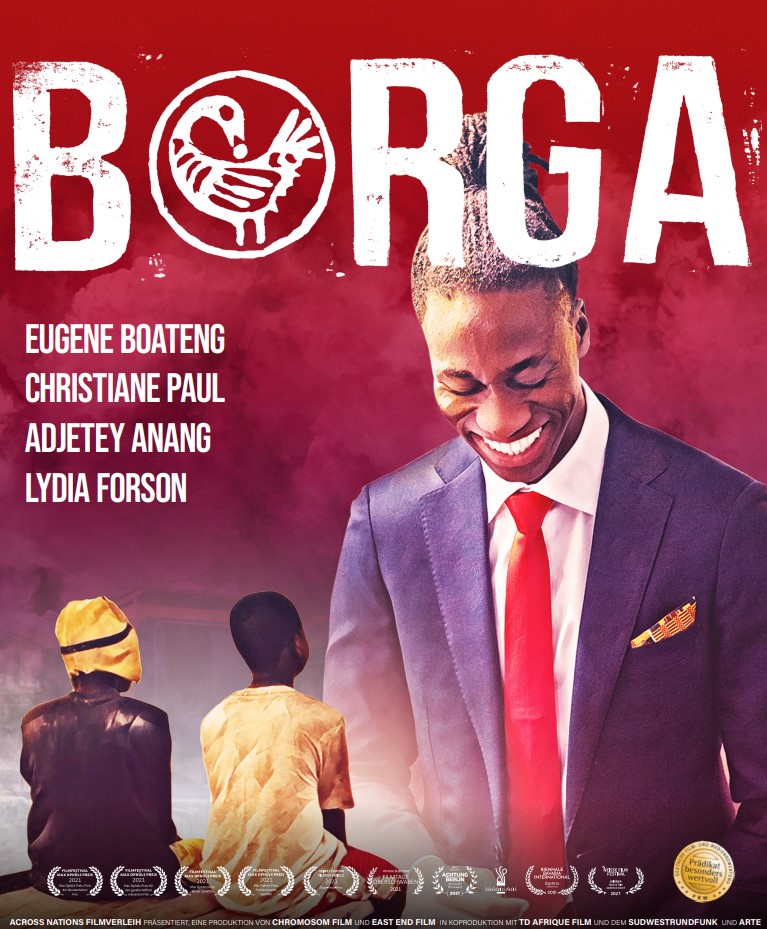

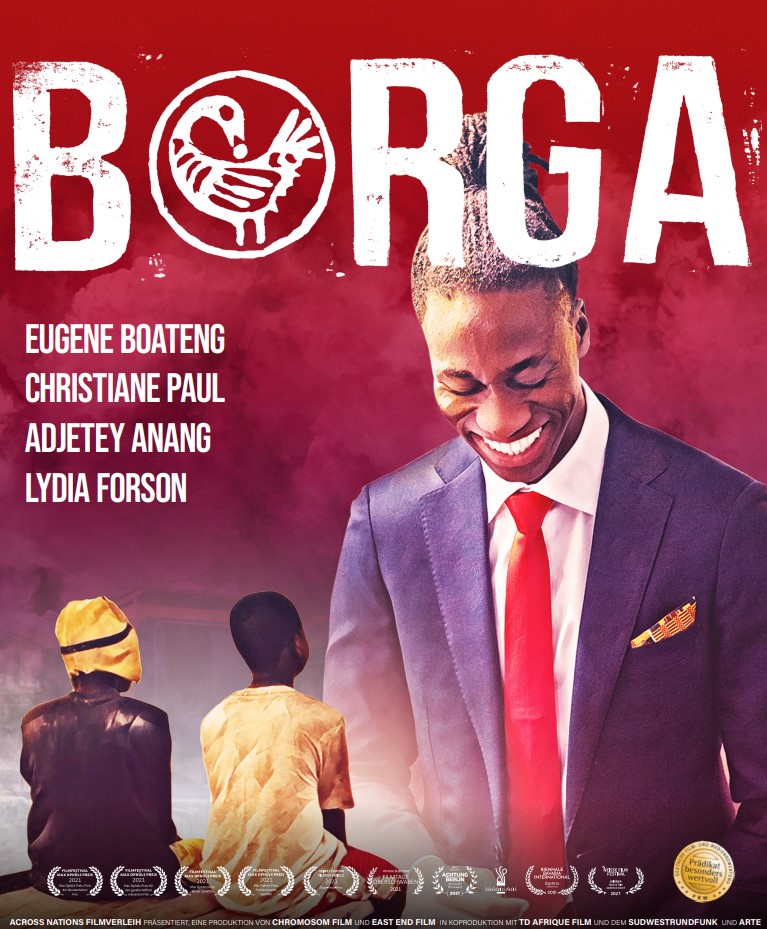

Borga – Much more than a Movie – Interview mit/with Director York-Fabian Raabe – ger/engl

Es steckt viel drin in diesem Film. Ein Film über eine Familie, über heimat, Migration, Rollenbilder, afrikanische Realitäten und Klischees. Die Herstellung, die Produktion auf Augenhöhe mit den SchauspielerInnen, der wahrhaftige Ansatz dieser Produktion gibt genügend Stoff für ein Gespräch. Mit York-Fabian Raabe habe ich mich unterhalten, Eugene Boateng konnte kurzfristig doch nicht. Es war ein interessanter Nachmittag.

HH: Du bist nicht der Versuchung erlegen, aus dem Film heraus eine White Savior Botschaft zu senden: Diese Apokalypse

dort in Accra mit ihren Menschen unwürdigen Verhältnissen muss ein Ende haben ?

YFR: Der Film ist so gebaut, dass er im Kern eine Message erzählt, die auf das westafrikanische Adinkra Symbol Sankofa

aufbaut: Dreht Euch um, guckt in Eure Vergangenheit, lernt daraus und nehmt das Gute aus der Vergangenheit und tragt es nach

vorne.

Aber wenn du Agbogbloshie als Ort meinst, ich bin Filmemacher und kein Entwicklungshelfer und ich bin auch kein

Prediger. Agbogbloshie ist ein sehr komplexer Ort. Für viele Menschen ist es auch ein Zuhause. Wenn du dort hingehst und

mit den Menschen drehst, redest, arbeitest, dann ist es erst mal deren zuhause. Und ich habe auch nicht das Recht darüber zu

urteilen, nur weil ich denke, hmm, die Tür schließt vielleicht nicht ganz luftdicht wie in Deutschland (ironisch). Dann heißt

das noch lange nicht, dass ich das Recht dazu habe zu sagen: Das ist schlecht. Ich versuche mich mit Bewertungen zurück zu

halten was Umstände angeht.

BORGA ist eine Herzens Geschichte und eine Familiengeschichte. Eugene und ich haben diesen Film gemeinsam auf

Augenhöhe erschaffen. Wenn es um den Cause geht, den wir wollen, dass alle Menschen gleich angesehen werden, dass die

Black Communities erstarken, ihre eigenen Sachen machen können, nicht mehr benachteiligt werden, was diesen Cause

angeht, da stehe ich nicht vorne. Ich find es nicht in Ordnung, wenn diese Themen von Nicht-Betroffenen vereinnahmt

werden, ich nenn es auch Hijacking. In Amerika passiert es ganz häufig, dass Themen gerne gehijackt werden. Weiße

Männer und Frauen hijacken die Themen von schwarzen Männern und Frauen.

Der Cause ist Eugenes Thema, da hat Eugene eine ganz andere Position als ich. Also bildlich gesprochen, ich helfe mit, den

Karren zu schieben, ich supporte. Aber ich stehe nicht vorne als Gallionsfigur, ich sitze auch nicht am Steuer. Ich schiebe

den halt. Und wenn er in eine komische Richtung fährt, würde ich vielleicht sagen: “Eh, das find` ich nicht gut.” Aber alles

andere steht mir nicht zu.

HH: Zur Sprache im Film; hat es viel Überzeugungsarbeit gekostet, dass der Film auch in Originalsprache mit UT ins Kino

kommt? In Deutschland wird ja gerne synchronisiert.

YFR: Wir habe Twi, Ga, Fanti und ein bisschen Hausa. Das es Deutsch synchronisiert würde, war nie ein Thema. Was wir

überlegt hatten war, Pigeon English sprechen zu lassen. Wegen der größeren Zugänglichkeit. Eugene hat darauf bestanden,

es auf Twi zu drehen. Bei den Castings haben wir gemerkt, dass wenn die Darsteller Twi sprechen auf einem anderen Level

spielen. Wir haben uns dann dafür entschieden. Im Nachhinein war es die richtige Entscheidung gewesen.

HH: Wie war denn die Zusammenarbeit mit Eugene Boateng. Er fungiert ja nicht nur als Schauspieler sondern war auch für

die kulturelle Beratung zuständig?

YFR: Wenn z. B, Eugene gesagt hat, die Skulptur in dem Afro-Shop in Mannheim, das passt nicht. Dann war diese Figur

danach weg.

Wenn es ums Schauspiel geht spüre ich aber meistens instinktiv vorher, wenn etwas nicht stimmt. Falls ich des Rätsels

Lösung nicht selber gefunden haben, bin ich zu Eugene und dann haben wir gemeinsam versucht das zu erforschen.

Wir haben, glaube ich, ein Problem in Deutschland mit der Definition von Regie. Da gilt immer noch: Der Regisseur hat als

einziger die Vision im Kopf und muss es schaffen diese Vision genau wie in seinem Kopf auf die Leinwand zu bringen.

Aber es gibt viele Arten Regie zu führen: Bei Michael Haneke gibt es Probleme, wenn die Satzkonstruktion nicht genau wie

im Drehbuch ist; Ron Howard dagegen hat die Methode „Directing by Contribution“. Und diese Art von Regieführung (von

Ron Howard) ist für einen Film wie BORGA unerlässlich. Weil der Erfahrungshorizont von Eugene, aber auch von den

anderen Schauspielern total wichtig ist. Und mit Eugene gab es eine Person, bei dem die ganzen kulturellen Faktoren

zusammenlaufen. Zusammen haben wir dann wiederum mit den jeweiligen Schauspielern die Feinheiten herausgearbeitet.

Ich habe den Gesamtüberblick und den Blick für die Inszenierung, Eugene den kulturellen Blick und die Schauspieler noch

mal ihren eigenen. Aus allem zusammen entstand diese besondere Authentizität des Films.

HH: Es gibt eine schöne Szene im Film, wie Eugene im strahlend blauen Anzug mit teuren Schuhen durch Agbogbloshie

läuft. Er scheint wie entrückt. Kannst du etwas zu der Bedeutung des Films für Eugene sagen?

YFR: Das kann nur Eugene selbst sagen. Ich kann aber einen kleinen Einblick geben, was ich beobachtet habe. Für Eugene

ist der Film eine ganz besondere Erfahrung. Er trägt zwei Heimaten in sich, die Ghanaische und die Deutsche. Wenn man

z.B gesehen hat, wie stolz er über seine Heimat in der Kiefernstraße in Düsseldorf spricht und dann wiederum genauso über

seine Heimat in Ghana, dann versteht man das.

Für den Film musste, wollte und konnte er in beiden Heimaten aufgehen und auch in beiden bestehen. Deswegen ist es für

ihn ein ganz besonderer Prozess gewesen. Er hat beide Seiten dabei auch neu kennen gelernt.

Zu der Szenen mit dem Anzug gibt es eine Anekdote; Eugene steht im Anzug auf der Brücke, wir drehen gerade, da kommt

ein Einheimischer und beschwert sich, dass wir wieder nur das Klischee (die Armut auf der Müllhalde und nicht das

wirkliche Leben der Menschen) zeigen. Eugene hat dann mit ihm gesprochen und die Idee des Films erklärt. Danach war er

begeistert.

An den Ort kommen nämlich viele Journalisten und machen einen “Leidenstourismus”. Das ist ein großes Problem. Sie

schaffen ein Mitleidsbild, von oben herab. Diese Mitleidsperspektive nimmt Respekt und Stolz.

HH: Du hast viel Kontakt zur Ghana Community in Deutschland. Wie nimmst du das Verhältnis der Menschen in der Diaspora war?

HH: In einem anderen Interview habe ich gelesen, dass Eugene die Rolle gar nicht erst spielen wollte, wegen der

vermeintlichen Klischeerolle, stimmt das?

YFR: Das ist eine große Fehlinformation! Er wollte das Drehbuch nicht lesen! Ein Jahr hat es gebraucht, dass ich ihn

überzeugen konnte, das Drehbuch zu lesen.

Man muss das verstehen. Da kommt ein weißer Regisseur und sagt: Ich hab hier eine afrikanische Geschichte für Dich. – Bis

dato hat er so viele schlechte Erfahrungen damit gemacht, er hatte einfach keinen Bock mehr auf die Mitleidsgeschichten.

Wir dagegen haben ihn belagert, haben ihm mails geschrieben… Dann haben wir ihn getroffen. Da hab ich zu ihm gesagt:

“Eugene, das ist ne Hauptrolle, eine super Geschichte. Lies‘ doch die ersten 15 Seiten. Wenn sie dir nicht gefallen, hau es in

den Müll!” Und er hat es gelesen und war hin und weg. „Wir müssen das machen. Sofort! York! Und das… und das…“ war

seine Reaktion.

HH: Mit deinem Film BORGA stellst du schon noch immer eine Ausnahme, was die Authentizität von Geschichten und

Rollenbildern aus Afrika betrifft, oder?

YFR: Das stimmt leider schon. Aber auf den ersten Blick könnte man BORGA auch vorwerfen, auch dort macht die

Hauptfigur ja nicht nur coole Sachen. Aber er macht diese aus gutem Grund. Das ist alles an realen Personen recherchiert. Es

wird also verstanden, warum Personen etwas tun. Und damit wird die Oberflächlichkeit genommen; “der schwarze Mann ist

der Drogendealer, nimmt die weißen Frauen weg”. Das wird bei Borga ausgehebelt, weil das Leben viel komplexer ist.

Ich finde es prinzipiell gut, wenn schwarze SchauspielerInnen alles spielen – alles! Vom Richter bis zum Gangster. Warum

denn nicht? Warum soll Scarface nur ein Weißer spielen dürfen? Man muss immer ein bisschen unterscheiden zwischen dem

Cause, also das man machen möchte, dass sich das Bild von schwarzen Menschen ändert und was einzelne Genres und

Personen sind, mit denen man sich emotional verbindet.

Wenn da zum Beispiel ein Mensch ist, der aus Liebe zu seiner Familie ganz viele Dinge über sich ergehen lässt, die dann

partiell auch noch nicht ganz legal sind, dann steht da vorne, dass das jemand aus Liebe macht. Da steht dann ein Held, der

alles über sich ergehen lässt, weil er es aus Liebe zu seiner Familie und den Glaube an seinen Traum macht. Das ist doch ein

anderes Bild, als wenn du einen schwarzen Verbrecher plakativ in einer deutschen Vorabendserie siehst. Menschen reden

gerne über das „Was“ und nicht so sehr über das „Wie“. Ich kann dir beispielsweise eine Anwaltsrolle schreiben, da

bekommst du das Kotzen. Ich könnte dir wahrscheinlich aber einen Mörder schreiben, der ein so emotional naher Mensch

ist, dass er ganz positiv rüberkommen würde. Also das „Wie“ ist viel entscheidender, als das „Was“. Und so gelangen wir

zur Authentizität.

HH: Müsste noch viel mehr passieren im deutschen Film, was Diversität angeht. An deutschen Bühnen ändert sich langsam

etwas, bekannte Ensembles wie das Berliner, Bochumer Schauspielhaus, Frankfurt haben schwarze Schauspielerinnen…

YFR: BORGA tut hier ein kleinen Beitrag, denn es tut sich was seit 2020/2021. Aber ich möchte hier in den Blick kurz in

die Zukunft richten. Auf der einen Seite habe wir als Filmemacher eine gesellschaftliche Verantwortung. Auf der anderen

Seite auch eine Verantwortung gegenüber dem Publikum, es zu unterhalten, abzuholen und interessante, authentische

Geschichten zu erzählen.

Hier liegt aber das Problem im deutschen Film bzgl. mehr Diversität. Wir brauchen auch gute Stories für unsere diversen

Schauspieler. Denn so richtig ans Herz geht es nur, wenn es tief in die Figuren geht. Dafür müssen die Rollen geschrieben

werden. Das ist nicht einfach. Es gibt also zu wenig gute Drehbücher.

Die Rückmeldung, die wir mit unserem Film von den Black Communities bekommen haben ist: “Ihr zeigt mit dem Film,

dass es ein Junge wie der Eugene schaffen kann, den Deutschen Schauspielpreis zu erhalten.”

Dieser Glaube, es schaffen zu können war bisher dort nicht immer da. Und das ist etwas, was Eugene mit ausgelöst hat. Das

da Bewegung und mehr Confidence in das eigene Tun kommt. Auf einmal kommen da Nachrichten aus den Communities:

„Wir wollen das auch machen, kannst du sagen, wie das geht?“

Und hier gibt es viele gute Stories! Was jetzt noch fehlt, sind handwerklich gut gemachte Drehbücher. Denn

Drehbuchschreiben ist ein zeitintensives Handwerk. Und die Confidence in den Communities erwacht ja gerade erst. Es wird

also ein bisschen Zeit brauchen, bis wir ein große Menge an guten Stoffe in guten Drehbücher bekommen. Dieser

Bewegungsprozess insgesamt braucht noch etwas Zeit. Und wir sollten hier supporten, gerade weil schwarzen Autoren

bisher oftmals die Türen verschlossen geblieben sind.

Eine wichtige Rolle spielen hier die Öffentlich-Rechtlichen Sender für die ich eine Lanze brechen möchte, ohne sie gäbe es

in Deutschland ein kulturelles Massaker. Aber so wichtig in diesem Prozess auch die Öffentlich-Rechtlichen Sender auch

sind, ich wünsche ihnen eins: Dass sie besser ihre Zielgruppen kennen lernen. BORGA zeigt das ganz gut. Es sind eben nicht

nur die Jungen, die den Film gut finden. Bei den Vorführungen gibt es auch eine große 60+ Zielgruppe, die auch auf den

Film steht. Das Publikum kann manchmal viel mehr ertragen als ihm zugetraut wird. Deshalb wünsche ich mir mehr diverse,

authentische Geschichten mit Tiefgang, ohne dabei die Unterhaltung zu verlieren; sowohl als TV Format als auch als Kino-

Koproduktion.

HH: Vielen Dank für das Gespräch!

ENGLISH VERSION

It has been in cinemas in Germany for just under two weeks: BORGA. The story of two brothers from Ghana, Kojo and Kofi. One of them will later set off for Germany, because a Borga, the name of the supposedly rich uncles who have made it big in a foreign country, has electrified him.

There is a sizzle from the very first second. The fire is lit right at the beginning. And it will draw us into the film and take us along with its emotional force. First Ghana, later Germany and back again. At the beginning the fire is burning: we are in an eerie and yet very real place in Africa. A place that has been the subject of several reports: Agbogbloshie, or Sodom and Gomorrah, is part of Accra, the capital of Ghana. It is this very real non-place, a sometimes apocalyptic place where people burn the raw materials out of the electronic waste of the global north.

But it is also a deeply humane place, which we can experience in “Borga” in a way that has never been shown before. Yet what we are allowed to experience in the film “Borga” is not a documentary. As director, York-Fabian Raabe has delivered a visually powerful feature film debut that is stirringly staged. Tobias von dem Bornes is responsible for the camera. The ensemble of actors is superbly cast: first and foremost, of course, Eugene Boateng. But also the other actors, some of them stars from Ghana (Adjetey Anang and Lydia Forson), but also a discovery of the film, the young Emmanuel Affadzi and from Germany Christiane Paul.

for supporting our authors there is a possibillity to donate

https://www.patreon.com/cultureafrica

There is a lot in this film. A film about a family, about home, migration, role models, African realities and clichés. The production, the eye-to-eye production with the actors, the truthful approach of this production gives enough material for a conversation. I talked to York-Fabian Raabe, Eugene Boateng could not make it at short notice. It was an interesting afternoon. From Hans Hofele

HH: We mainly talk about the film. When I thought of the questions, I assumed that Eugene I assumed that Eugene would be there. Maybe you can answer one or two of them for him. But let’s start with the making of the film. The production has been in the making since 2011. Why don’t you tell us how the film came about.

YFR: You should tweak this story: the core of the story is a family core. It’s about being the younger brother. Finding the approval of the family. That’s what both Eugene and I have in common, albeit in different ways. in different ways. Eugene as part of a big family, I’m the youngest and I have two bigger brothers who are 7 and 10 years older than me.

When you’re young, you want recognition, you want to keep up, but you’re not yet able to because of your development. not yet able to. When I was seven, my big brother turned 18. That’s the family core, which, funnily enough, is found funny enough, it happens all over the world. This is also the story of our producer Alexander Wadouh, his father and his brother. father and his brother. This story is spread all over the world.

HH: So there is a lot of universality in it. Ultimately also the reasons why Kojo comes to Germany; emigrates or seeks his fortune elsewhere.

YFR: I have to really praise you now because you say emigrate. Most people say flee. It is imprecise to say “flee”; it gives a wrong picture. There is a big difference between fleeing and emigrating.

HH: When I saw the film, I saw the universal motif of emigration: The father favours the The father prefers the eldest son, for the one or ones left behind there is not enough for a good life. This is a motif that is also Germany, e.g. in my homeland of Württemberg in the 19th century, was the central motive for emigration. The remaining inheritance in a barren region is not enough to live on. Was this motif also present in the film?

YFR: I was fascinated when I saw “The Other Homeland” by Edgar Reitz (German director, among others “Heimat”, note HH) for the first time recently, how many motifs coincide with Borga. At that time, in the 19th century, many Hunsrückers emigrated to Brazil. So there is scene with Kojo (the younger brother), who meets Borga, glorifies him and awakens in him the desire to emigrate. and awakens in him the desire to emigrate. In the “Other Homeland” the nobleman gives Jacob (also the younger brother) a travel book, which further inflames his longing for faraway places. I believe that we humans have much more in common than we think. I have a travel-crazy mother who took me to all sorts of countries from the age of 5. What I what I have seen above all: Societies are different, value concepts are different, but the human essence is what connects us in functioning societies. that is the unifying factor in functioning societies. And that’s why it doesn’t matter what continent, what colour skin colour. Borga comes from the word Hamburg, which means those who went to the West and became prosperous – and then returned. and then return. An Albanian spectator said to me, “In our country they are called Schatzis”.

HH: What happened next? From from the idea to the production?

YFR: The activation energy came from Stefanie Groß from SWR. I had won the Max Ophüls Prize in 2011 with my short film. short film. Stefanie saw it and said, “I would like it if we made a film”. Then I said, “OK. Then I’ll start thinking about it.” I already had ideas, fragments, but she initiated the film. initiated the film. HH: you also made a documentary about Agbogbloshie, was that before? YFR: During the research. I used to be a student at the DFFB. Reinhard Hauff was our director at the time. He used to say to us students: if you see a story and you have a camera with you, stop for a moment, think about a concept and then think about a concept and then start shooting. That’s exactly what we did.

HH: So what was it like shooting on location in Accra, in that particular place, were people suspicious when you showed up? showed up there? Were you welcomed or was it difficult?

YFR: What do you mean by difficult? Physically, it is a challenge. In terms of toxicity, it’s a tough act to follow. number. You have this combination of combustion toxins, then you have chemical toxins, then you have a lot of biological toxins. biological toxins. Layer by layer, biological and chemical hazards stick together. So blatantly that you can you can feel the pollution in the air miles away. The circumstances were tough. As far as the human aspect is concerned, what I have noticed so far about the people in Ghana is that they welcome you very politely. very polite; and if you come with respect, they treat you with respect. The same goes for this place. We had partners on the ground, and they in turn knew the chiefs. Agbogbloshie is divided into several areas; you go then go to the respective chiefs, pay them respect and also give them money. By the way, I don’t think that’s reprehensible. In Germany you also pay for filming permits. Once the deal is done, everything happens quickly. everyone knows about it. Everyone knew that it was OK if we shot.

HH: How did the cast come about, since there are also amateur actors?

YFR: The cast surprised me so much, I’m still happy, even though it’s so heterogeneous: Adjetey Anang and Lydia Forson are superstars; Adjetey is like George Clooney in Ghana. On the other hand, the little boy with the yellow cap in the film is a real street kid. We worked with an organisation that takes care of street children. street children. They placed the children with us. There were caretakers for the children on the set, that was important to us. And also fees were deposited for the children. The young leading actor, young Kojo (Emmanuel Affadzi), on the other hand, is an absolute professional! He came to me and asked: “Director, has something changed this day? No?! Okay then I am going to concentrate on these lines.” This I have hardly ever seen such a work ethic in a German actor.

HH: About the language in the film; did it take a lot of convincing to get the film into the cinema in the original language with UT? come to the cinema? In Germany, people like to dub.

YFR: We have Twi, Ga, Fanti and a bit of Hausa. That it would be dubbed into German was never an issue. What we What we thought about was having Pigeon speak English. Because of the greater accessibility. Eugene insisted to do it in Twi. In the auditions, we realised that when the actors speak Twi, they play on a different level. on a different level. We then decided to go for it. In retrospect, it was the right decision.

HH: What was it like working with Eugene Boateng? He not only acted but was also responsible for the cultural advice? responsible for the cultural advice?

YFR: For example, when Eugene said that the sculpture in the Afro-Shop in Mannheim didn’t fit. Then this figure was gone. But when it comes to acting, I usually instinctively sense beforehand when something is wrong. If I haven’t found the If I didn’t find the solution myself, I went to Eugene and then we tried to find out together. I think we have a problem in Germany with the definition of directing. It’s still the case that the director is the only one The director is the only one who has the vision in his head and must manage to bring this vision to the screen exactly as it is in his head. But there are many ways of directing: With Michael Haneke, there are problems when the sentence construction is not exactly as in the script. in the script; Ron Howard, on the other hand, has the “Directing by Contribution” method. And this kind of directing (by Ron Howard) is essential for a film like BORGA. Because the experience of Eugene, but also of the other but also of the other actors is totally important. And with Eugene there was one person where all the cultural factors all come together. Together we then worked out the subtleties with the respective actors. I have the overall view and the view of the production, Eugene has the cultural view and the actors have their own. their own. All together, this special authenticity of the film emerged.

HH: There’s a beautiful scene in the film of Eugene walking through Agbogbloshie in a bright blue suit with expensive shoes. in a bright blue suit with expensive shoes. He seems enraptured. Can you say something about the meaning of the film for Eugene?

YFR: Only Eugene himself can say that. But I can give a little insight into what I observed. For Eugene the film is a very special experience. He carries two homes, the Ghanaian and the German. When you proudly talk about his home in the Kiefernstraße in Düsseldorf and then again about his home in Ghana, then you understand that the his home in Ghana, then you understand that. For the film, he had to, wanted to and was able to merge and exist in both homelands. That’s why it was a a very special process for him. He also got to know both sides in a new way. There is an anecdote about the scene with the suit; Eugene is standing on the bridge in the suit, we are shooting, and a local comes and complains. and complains that we are only showing the cliché (the poverty on the rubbish dump and not the real life of the people). real life of the people). Eugene then spoke to him and explained the idea of the film. After that he was enthusiastic. Many journalists come to the place and do “suffering tourism”. This is a big problem. They create an image of pity, from above. This pity perspective takes away respect and pride.

HH: You have a lot of contact with the Ghana community in Germany. How do you perceive the relationship between the people in the diaspora?

YFR: I can only describe my observations here, which are neither generally valid nor meant to be judgmental in any way. judgemental. This is a complex field. The word diaspora alone already sets a perspective. For many, however, Germany is Germany is their home and the word diaspora makes less sense in this context. For me, the people with people with African roots in Germany. Were they born in their country of origin or not? Have they lived there? How did they deal with living in a “new” country, or how do their children deal with it, if the new country is their home, or not? Especially in Germany I see it with the Ghanaians, with our ideas: One half knows Twi (or another Ghanaian language) and is still very connected to the Ghanaian culture and the others cannot. Everyone has their own view and their own conflict. But I would always always connote it positively. There is movement, people are coming to terms with it, a consciousness is being formed and that is the great thing.

HH: In another interview I read that Eugene didn’t even want to play the role because of the supposed cliché role. because of the supposed cliché role, is that true?

YFR: That’s a big misinformation! He didn’t want to read the script! It took me a year to convince him to convince him to read the script. You have to understand. A white director comes and says: I have an African story for you. – Up to Until then he had had so many bad experiences with it, he just didn’t feel like doing it anymore.

HH: Much more needs to happen in German film as far as diversity is concerned. Things are slowly changing on German stages. well-known ensembles like the Schauspielhaus in Berlin, Bochum, Frankfurt have black actresses…

YFR: BORGA is making a small contribution here, because something has been happening since 2020/2021. But I would like to look briefly into the future. the future. On the one hand, we as filmmakers have a social responsibility. On the other On the other hand, we also have a responsibility towards the audience to entertain them, to pick them up and to tell interesting, authentic stories. stories. But this is where the problem lies in German film with regard to more diversity. We also need good stories for our diverse actors. Because it only really gets to the heart when it goes deep into the characters. The roles have to be written be written. That is not easy. So there are too few good scripts. The feedback we have received from the Black communities with our film is: “You show with the film, that a boy like Eugene can make it to the German Drama Awards.” This belief that he can make it was not always there before. And that is something that Eugene helped to trigger. That that there is movement and more confidence in one’s own actions. All of a sudden there are messages from the communities: “We want to do this too, can you tell us how to do it?”

And there are many good stories here! What is still missing are well-crafted scripts. Because Screenwriting is a time-consuming craft. And confidence in the communities is only just awakening. So it will a bit of time until we get a large amount of good material in good scripts. This This movement process as a whole still needs some time. And we should support it here, precisely because black authors have the doors have often remained closed to black authors. The public broadcasters play an important role here; without them there would be a cultural massacre in Germany. cultural massacre in Germany. But as important as the public broadcasters are in this process, I wish them one thing. I wish them one thing: that they get to know their target groups better. BORGA shows that quite well. It is not only only the young people who like the film. At the screenings there is also a large 60+ target group that also likes the film. the film. The audience can sometimes take a lot more than they are given credit for. That is why I would like to see more diverse, authentic stories with depth, without losing the entertainment; both as a TV format and as a cinema co-production.

HH: Thank you very much for the interview!

Copyright: cultureafrica 2021/HH

You May Also Like